April 17 | Stay in the Know with Ryan Goodman on Just Security’s Trump Administration Litigation Tracker

Welcome to the first installment of the Trump Administration Litigation Tracker Newsletter! I’ll be providing major updates and key takeaways, distilled for busy readers. We are monitoring the status of every case against Trump administration executive actions in the Tracker over at justsecurity.org. I will be sharing my own lessons about the litigation here.

I. Litigation snapshot:

The Just Security team has produced an initial set of infographics that are intended to help readers understand the status of the cases filed to date and how the American legal system is responding.

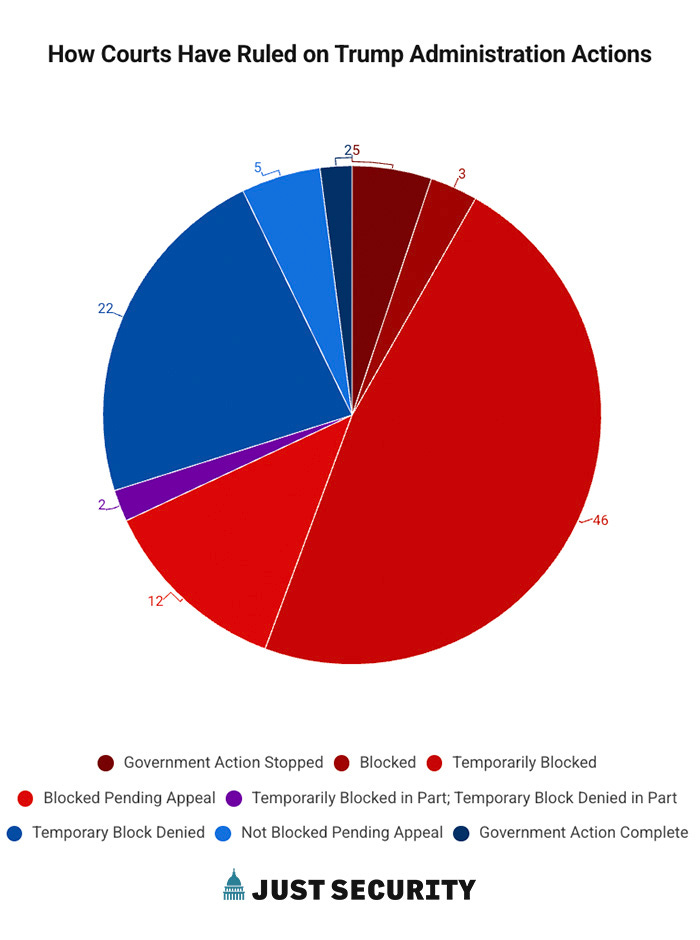

Let’s break down the first infographic, a pie chart. It shows 95 cases in favor of either the plaintiffs or the government (we removed cases awaiting a ruling or that have been closed or transferred):

In 66 cases plaintiffs have had at least some success in blocking the government’s actions – for example, by getting the courts to issue a temporary restraining order or a preliminary injunction. These cases are represented by the slices of the pie with shades of RED.

o In 53 of these cases, the government’s actions were either temporarily blocked (46) or blocked pending appeal (12).

o In 8 cases, government action stopped (5 cases) or was blocked (3 cases involving not TROs or preliminary injunctions, but instead permanent injunctions or summary judgment for the plaintiffs).

In 29 cases, the government has had success. In 27 cases, represented by shades of BLUE slices of the pie, the plaintiffs’ request to block government action was either denied (22 cases) or has been denied pending appeal (5 cases). In another two (2) cases government action has been completed.

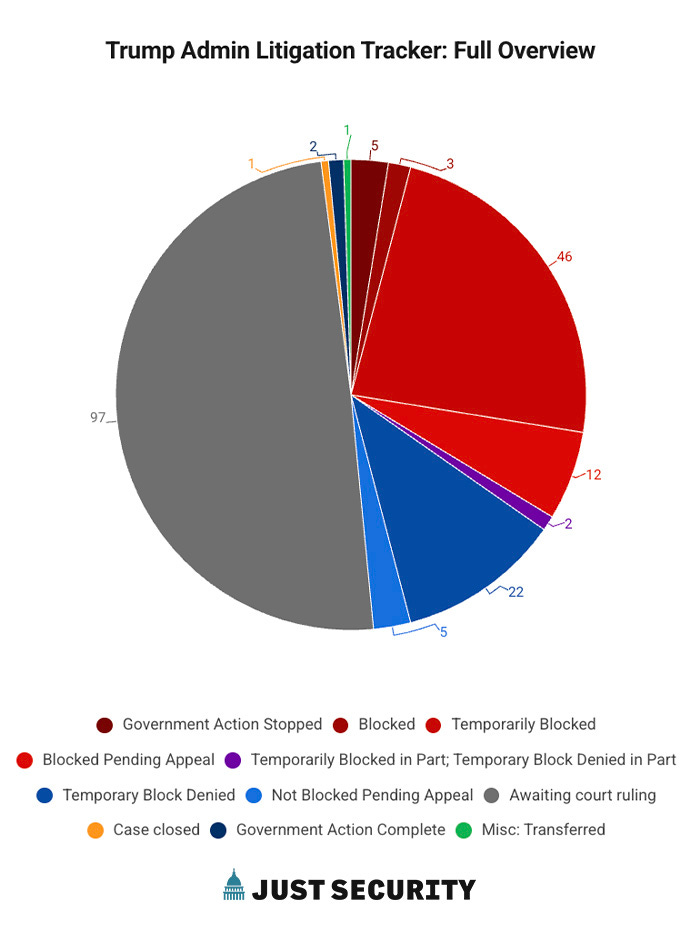

What do the pie charts show us? Plaintiffs have won more often than they have lost. As explained above, the plaintiffs have had at least some success in blocking the government’s actions in 66 cases. That is about 68 percent of the cases in the chart. In contrast, the government has won just 29 of these cases – or a little less than 30 percent of the time. A caveat here: these are, in many instances, early stages in the litigation and these percentages could change as the lawsuits progress through the courts. Indeed, the second pie chart also shows how many cases are still awaiting an initial court ruling.

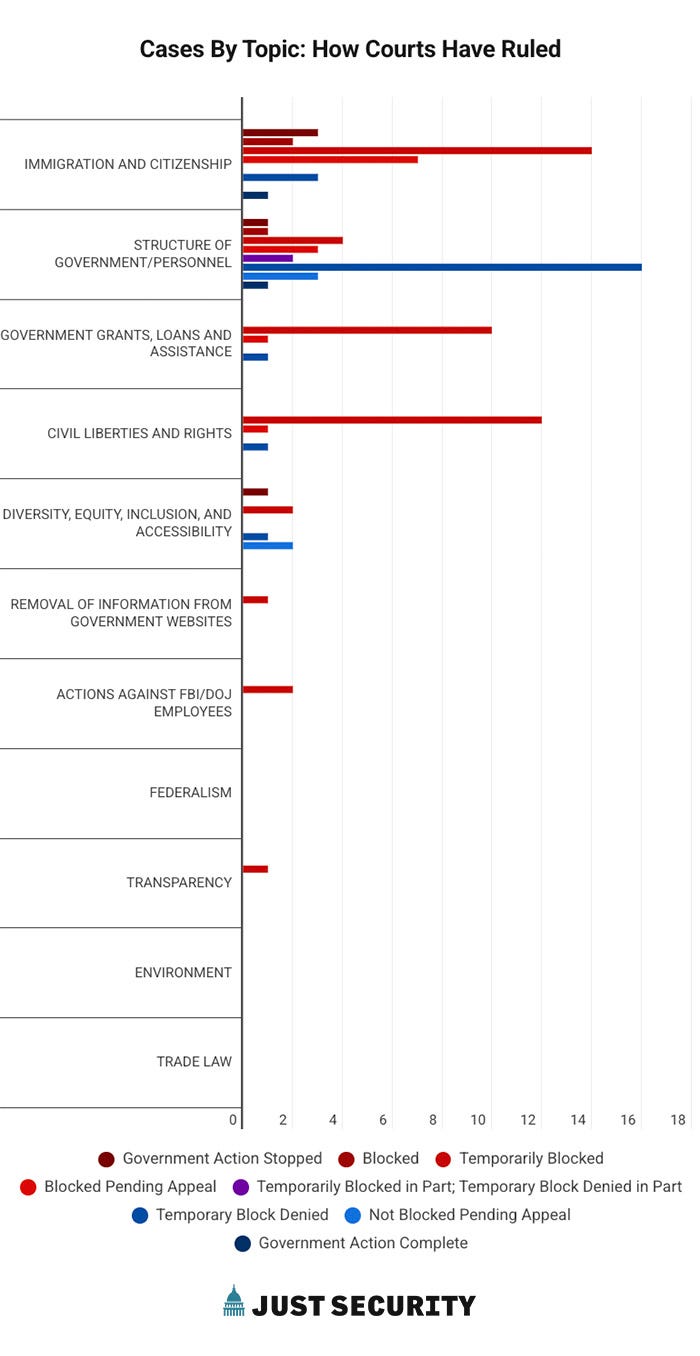

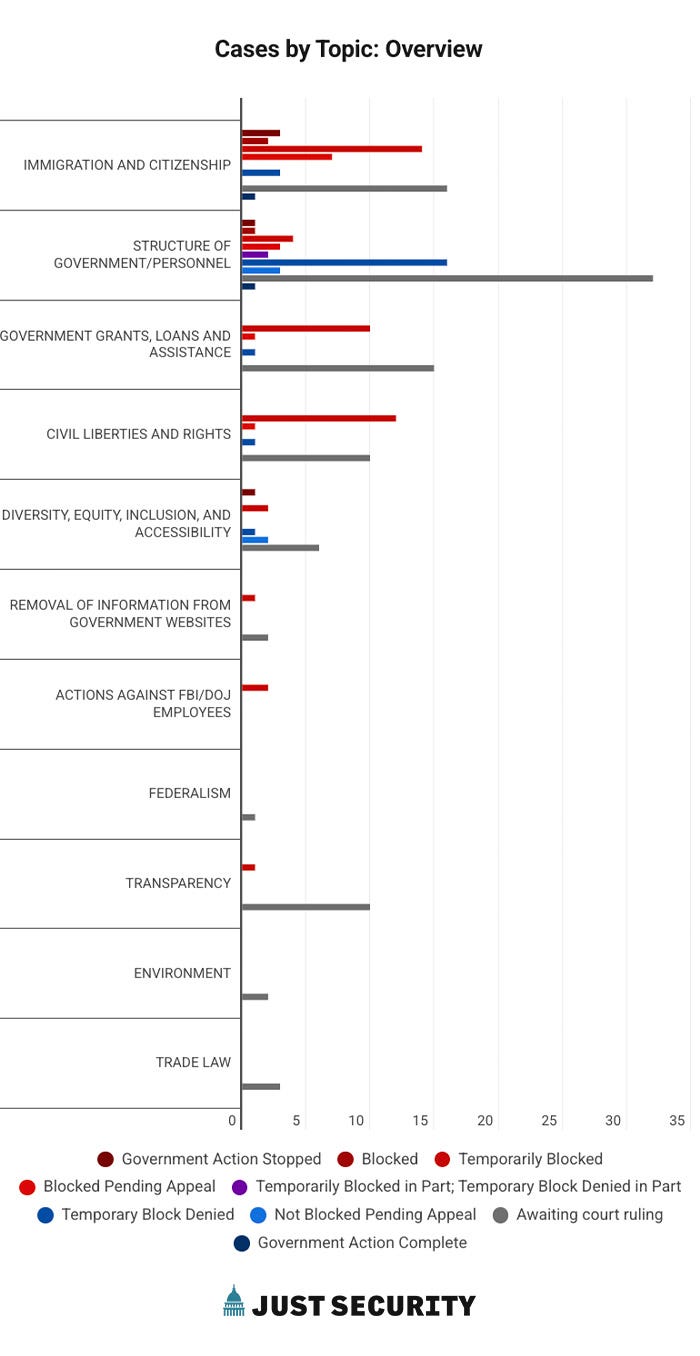

The infographic bar charts break down the cases by type. Presenting the data this way reveals some interesting nuggets of information.

For example, the bar charts show that there are more cases involving the structure of the U.S. government or personnel than any of the other types of cases in our data. The second bar chart shows more than 32 cases involving the structure of government and/or personnel are still awaiting a court ruling. Immigration and citizenship-related cases have the second greatest number of cases awaiting a ruling with just 16.

The bar charts allow us to see the types of cases in which the plaintiffs or the government have been most successful. The charts show that the government has been more successful in cases involving government structure or personnel than in any other type of case. Put another way: Plaintiffs have failed to temporarily block government actions in these types of cases more than any other types of cases.

However, plaintiffs have had far more success in temporarily blocking government actions in cases involving immigration and citizenship; government grants, loans and assistance; and civil liberties and rights.

In future newsletters, I will also discuss what infographics like these can and cannot tell us. Thanks for these infographics goes to my wonderful colleague, Pooja Shah, Just Security’s Director of Partnerships and Marketing.

II. My key takeaways for today: Contempt and what comes next

This week presents a true test for the rule of law in the United States. The key issue for this Thursday, April 17, must be – given the gravity of the situation – the crisis presented by two judges’ back-to-back findings that Trump officials engaged in “wilful disregard” and clear violations of their court’s orders. Both cases emanate from the administration’s sending people to the notorious CECOT prison in El Salvador.

Twenty-four hours before the publication of this Newsletter, the United States crossed into a new frontier. A DC district court judge held that he has probable cause to find executive branch officials acted in criminal contempt of court orders. Chief Judge James Boasberg wrote, “Defendants provide no convincing reason to avoid the conclusion that appears obvious from the above factual recitation: that they deliberately flouted” the court's command not to transfer purported Alien Enemies Act detainees into the hands of a foreign country. Full stop.

Wednesday's ruling by Boasberg followed on the heels of an order by Judge Paula Xinis, in a separate case in Maryland, who wrote that “Defendants have not yet complied with this Court’s directives, and Abrego Garcia appears to remain inexplicably detained in CECOT.” Another full and harrowing stop.

How quickly we’ve slid down this slope. It was just over a week ago, when the Fourth Circuit upheld Judge Xinis’s original order, that Reagan appointee Judge J. Harvie Wilkinson III warned in a concurrence that the government’s assertion that there is nothing that can be done to facilitate Abrego Garcia’s return puts the government on a dangerous path: “it takes no small amount of imagination,” he wrote, “to understand that is a path of perfect lawlessness.” The Wall Street Journal’s Editorial Board quoted Wilkinson in its own criticism of the president.

Judge Wilkinson and the WSJ Board wrote those warnings before the Supreme Court backed up Judge Xinis and blessed her order to “require[] the Government to ‘facilitate’ Abrego Garcia’s release from custody in El Salvador and to ensure that his case is handled as it would have been had he not been improperly sent to El Salvador.” The government now stands in violation of that Supreme Court ruling (which had no dissents) and the district court order adhering to it. Plus the Supreme Court had already ruled unanimously in an appeal from Judge Boasberg’s case that everyone ripped from our shores to prison in El Salvador was entitled to a pre-removal hearing.

What comes next?

The two El Salvador prison cases and the district court judges’ approaches now work in tandem.

Absent a stay from the appellate courts, we will likely see judicial fact-finding in the weeks, not months, ahead. Judge Xinis has set in motion an expedited discovery process (to be wrapped up in 2 weeks) to determine whether government officials acted in “bad faith” in defiance of her order. That includes the production of documents, affidavits, and depositions. For his part, Judge Boasberg is quite likely to enter a fact-finding process – including “hearings with live witness testimony under oath or to depositions by plaintiffs” – to determine who in particular in the White House or elsewhere may have criminally approved the violation of his orders. (That’s assuming the government does not take Judge Boasberg’s proposed off-ramp of giving the detainees held in El Salvador access to habeas proceedings by next week.)

The Government’s triple bind

The government is in multiple binds here. If it takes Judge Boasberg’s offer to rectify the contempt “by asserting custody of the individuals” (the judge’s words) for the purpose of habeas proceedings, the administration will be admitting it can “deliver the body” (the heart of habeas corpus) – and thus contradict its claim before Judge Xinis and the world that its powerless to facilitate their release. Meanwhile, revelations in Judge Xinis’s fact-finding process may leave the government with no excuse to avoid rectifying the criminal contempt in the method Boasberg proposed.

What’s more, last night, the ACLU and Democracy Forward informed Judge Boasberg that they intend to bring a habeas claim seeking the return of the men held in CECOT, especially now that the Supreme Court has ruled (9-0) that they deserved a constitutional right to notice and reasonable time to file a habeas petition before being deported under the Alien Enemies Act. Working in their favor is a 2004 decision by DC district court Judge John Bates finding habeas applied to a U.S. citizen held in a Saudi prison (for more on that, see Steve Vladeck’s substack post). The government will likely argue that a 2010 DC Circuit case finding habeas did not extend to foreign nationals held at a U.S. military base in Bagram, Afghanistan works against plaintiffs’ arguments. But that case turned on the fact the detainees were held in an active warzone, and is likely distinguishable on a number of other grounds. (We will have more analysis of these cases in a legal deep dive at Just Security.)

What many of these boiling issues will come down to is whether the U.S. government can be shown to have “constructive custody” over the detainees in El Salvador. If so, bad faith behavior of officials will be manifest, and we will likely see another contempt order this time from Judge Xinis. That path to demonstrated lawlessness will amplify the constitutional crisis at hand. But it will also open up a path for the detainees in El Salvador to exercise their right to get a judicial hearing.

III. Keep your eye on the ball:

One of the most important cases for the rule of law and the role and function of independent agencies may be decided any day now by the U.S. Supreme Court. The Court has before it two combined cases that involve the president’s attempted removal of members of the National Labor Review Board. This is not one of those situations in which it’s easy to predict the outcome. Chief Justice Roberts has signalled he might support a fundamental shift in how much power presidents have in this space.

The case presents the Supreme Court with the opportunity to overturn a landmark 1935 opinion, Humphrey’s Executor. That decision unanimously held that the president does not have the power to dismiss officials of a multi-member quasi-legislative or quasi-judicial administrative body without cause if Congress has passed a statute forbidding it. I asked Professor Rick Hills, a colleague of mine and a foremost expert on this area of law, to explain the stakes of the NLRB case for Newsletter readers. Here’s what Rick wrote:

“Two institutions stand or fall with the principle that Congress can prohibit the President from firing agency chiefs without a good reason: Our civil service system, and our monetary system. These institutions practically define rule of law and financial stability.

“The civil service system depends on the independence of the Merit Systems Protection Board from the President. The MSPB adjudicates civil servants’ complaints of arbitrary, partisan, or other abusive adverse action. If the MSPB’s members serve at the pleasure of the President, then the judge and prosecutor are one and the same, and the workforce of the federal government will resemble Boss Tweed’s machine.

“The monetary system depends on the independence of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors from the President. The Fed oversees the United States’ monetary policy that determines banks’ interest rates and critically affects employment and inflation. Every modern, industrialized democracy understands that elected executives have incentives to juice interest rates for short-term electoral gains, which is why they all have independent central banks. If the Board of Governors serves at the pleasure of the President, our monetary system will devolve into Juan Perón’s Argentina, prone to politically driven hyperinflation and recession. And investors know this.”

On April 9, per Chief Justice Roberts, put a temporary hold on the DC Circuit’s en banc (full court) decision to keep the NLRB members in their positions on the Board pending the outcome of litigation. We now await the Supreme Court decision whether to keep that hold in place and what they might signal about the merits of the litigation. The administration submitted what should be its final brief to the Court just yesterday.

IV. What I’m reading and watching:

I recommend watching Andrew Weissmann’s video explainer of Judge Boasberg’s order and the nuances of civil versus criminal contempt. Reading the Wall Street Journal Editorial Board’s criticism of Trump’s attacks on Harvard. And Steve Vladeck’s prescient assessment of plaintiffs’ filing habeas claims in DC for detainees held in El Salvador.

V. From the mailbox:

I’ll be answering readers’ questions. Email me any questions on your mind about the ongoing litigation, and I’ll pick a few each week to respond to in this newsletter. (And, once again, if you don’t mind my mentioning your name in a future newsletter please say so in your email, otherwise I’ll consider any comments anonymous.)

Make sure you check the Litigation Tracker at justsecurity.org regularly for updates and let us know if we’re missing anything.

Thank you for being part of the Just Security community,

Ryan

Every single Senator and Congressperson needs to receive a copy of this tracker.

Is it not the case that embedded in Judge Wilkinson's opinion is the CRITICAL proposition that the greatest RISK of the Garcia case is Admin' assertion that it may, without benefit of ANY remedy or judicial review, effect a Denial of Due Process to ANYONE? Specifically, in this instance. the unique structure of the Alien Enemies Act permitting an individual to be DEPORTED is being here applied to effect the targeted individual to be PUNISHED (incarcerated) without ANY recourse, I.e. WITHOUT DUE PROCESS of law? And. as his opinion suggests, nothing in the Administration's evidence limits its intended application of the statute to any class of person, clearly concluding that this denial of Due Process may be applied to any U.S. Citizens!